App Pop-Up Bars Enforceability of Arbitration Agreement

After waiting more than 5 minutes for an Uber ride to show up, Julian Metter called the driver, only to learn the driver could not make it. The driver instructed Metter to cancel the ride and order a new one. Unbeknownst to Metter, he was charged $5 for cancelling the ride, even though the driver had told him to do so. He filed a Federal class action law suit on behalf of himself and others who had been charged cancellation fees by Uber under similar circumstances. Relying on its “Terms of Service,” Uber filed a motion to compel arbitration. That’s where things got interesting.

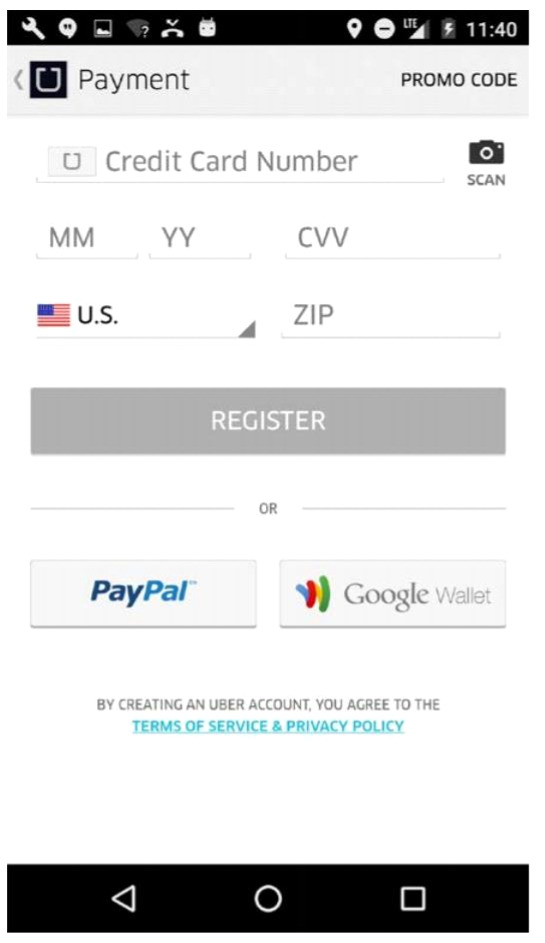

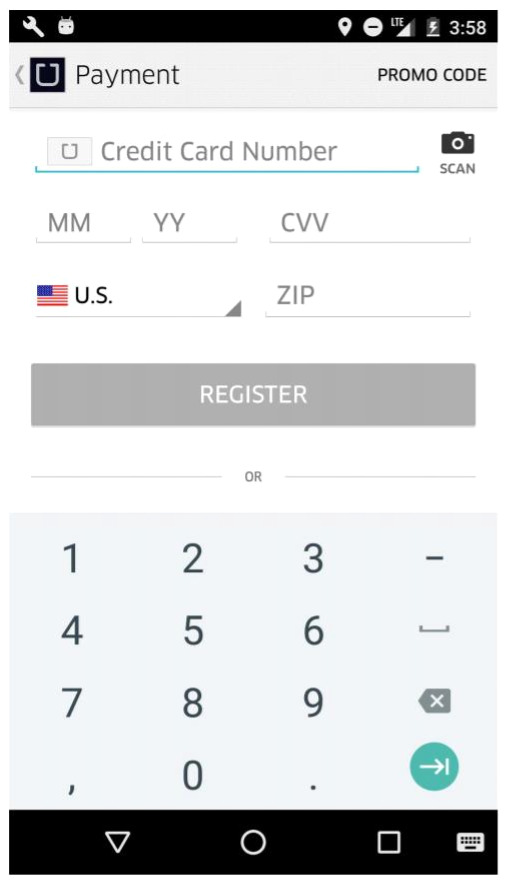

The Federal District Judge ruling on Uber’s motion noted its role was limited to ruling on 2 issues, namely whether a valid agreement to arbitrate exists and whether the agreement encompasses the dispute at issue in the case. Uber argued that by creating an account, Metter agreed to its Terms of Service, which included the arbitration provision. The Judge focused on how the app operated, however, noting that to create an account, Metter had to enter his credit card information, and when he did so, a key pad popped up over the hyperlink to the Terms of Service, leaving only the credit card entry fields and the “Register” button exposed. Metter argued that this arrangement gave him no reason or opportunity to see the Terms of Service link, which the Court noted was otherwise prominent were it not for the keypad popping up over the Terms of Service link, and so, he had no opportunity to review and agree to the Terms of Service.

The Court noted “When such a registrant presses ‘REGISTER’ without having seen the [agreement to the Terms of Service] alert, he does so without inquiry notice of Uber’s terms of service and without understanding that registering is a manifestation of assent to those terms.” The Court therefore concluded that the keypad obstruction was a fatal defect in the app to the function of the Terms of Service alert, and therefore, it held that it was impossible to conclude on the facts before it that Metter had been on inquiry notice of the Terms of Service and had affirmatively assented to them. The Court was careful to distinguish the case from those where a claimant has not seen the Terms of Service simply because the claimant did not bother to read them; in this case, the function of the Uber app effectively prevented Metter from seeing those terms. Therefore, the Court denied the motion. The lesson here is where the Terms of Service matter, and they normally do, it is important that they be prominently displayed so that they can be viewed and that the person confronted with the terms of service be given a meaningful opportunity to review them and indicate consent to those terms before proceeding. This is often done by clicking a box indicating consent to the terms or something similar. Uber may have learned this lesson the hard way.